Strategy is a conscious choice of a specific direction of development that allows a company to focus on defined goals and use available resources effectively. The essence of strategy lies in deciding which actions and areas of activity are priority and which should be limited or eliminated. Thanks to this, a company can concentrate on perfecting the chosen path, minimizing operational chaos and increasing its competitiveness.

In Poland, many bakeries use a mixed model in which part of the products are sold to external stores (wholesale or retail), part goes to supermarkets, and the remaining portion is sold through a network of their own brand stores.

At first glance, such a model seems flexible and opens many distribution channels, but in practice it often leads to operational inefficiency. The reasons include:

Divergent requirements. Each of these sales channels requires a different approach. For example, working with supermarkets demands large volumes at low margins, whereas sales in own stores involve maintaining staff and premises.

Resource dispersion. Managing diverse sales channels requires different resources such as a transport fleet, staff, or marketing strategies.

Increased workload. Combining these activities raises the number of operational processes that must be coordinated, which increases the burden on employees and owners.

Difficulty in optimization. By focusing on many directions at once, the company struggles to achieve maximum efficiency in each of them.

Choosing one coherent strategy is a key element of effective management and long-term success. It allows the company to focus on perfecting specific processes and actions, which improves their quality and efficiency. With a single strategy, the company can optimize the use of resources such as people, finances, or infrastructure, eliminating unnecessary costs. Finally, the most important argument—specializing in one area of activity enables building a competitive advantage, e.g., through better product quality, faster customer service, or lower operating costs. In short, a unified strategy reduces operational complexity, making planning, control, and performance monitoring easier.

[pdf-embedder url=”http://sigmaquality.pl/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/W-MOSZCZYNSKI-ppic-1-25.pdf” title=”W-MOSZCZYNSKI ppic 1-25″]

Strategic Planning

Let us imagine a situation in which a bakery has grown significantly. From its profits, the owner has built a large plant for the production of bread and pastries. At a certain stage of development, they must decide which strategy to adopt. There are four options.

Strategy 1: Cooperation with supermarkets

This strategy consists of supplying large quantities of bread at very low margin. Supermarkets impose the size and type of production, and settlements with the entrepreneur take place with a substantial delay. In addition, the entrepreneur must invest in a fleet of vehicles to enable long-distance transport. This requires hiring drivers and vehicle maintenance staff. Although the margin in this model is very low, it provides stable income.

Strategy 2: Creating a network of own stores

The owner can open a network of their own shops in nearby towns and villages. These shops would be rented, which entails leasing costs. It is also necessary to create a vehicle fleet and hire drivers and mechanics. Additionally, store staff must be maintained as part of the bakery’s workforce. In this model, planning and the development of sales strategies are required. The margin here is higher than in cooperation with supermarkets, but managing a network of stores is more labor-intensive and involves greater instability (e.g., due to lease agreements or staffing).

Strategy 3: Cooperation with external stores

The bakery supplies bread to external stores whose staff are not bakery employees. These stores accept the goods, and if they do not sell the bread, they return it to the producer. The bakery owner must have a fleet of vehicles and hire drivers and technical personnel to service the fleet. In this model, sales are planned by the external stores, and the bakery merely fulfills their orders. The profitability of this model is higher than cooperation with supermarkets, but lower than in the case of running own stores. However, the model is characterized by high stability.

Strategy 4: Wholesale or sales through intermediaries

The bread producer manufactures goods that are then put up for sale. Buyers come to the receiving hall, where they purchase products based on daily market prices or auctions. A similar model existed at Poznański’s Manufaktura in Łódź, where traders came from all over the country to buy large batches of goods.

In our case, a model of sales through intermediaries can be considered. The bakery signs contracts with intermediaries who collect the bread and distribute it further. In this model, the bakery does not have to employ store staff, drivers, or maintain a vehicle fleet. Production is based on orders from regular customers, which limits the need for sales planning. Profits are smaller, but the model is simpler to manage and less demanding operationally.

Each of these strategies has its advantages and disadvantages, so the choice should be well thought out, taking into account the bakery owner’s capabilities and goals.

People and Their Choices…

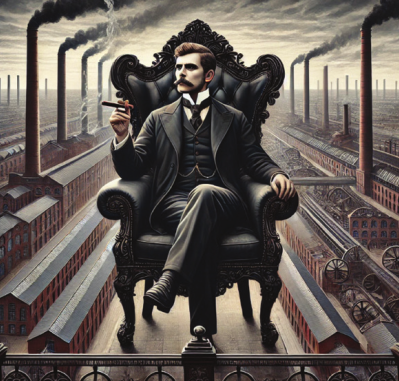

Now comes the moment of choosing a strategy. The wholesale vision appeals to me the most. I imagine myself sitting in a leather, tufted armchair, cigar in hand, watching from a high, glass-walled office as intermediaries’ trucks pull up to the loading dock. Everything is under my control: flour in the warehouses, employees under the watchful eye of cameras, and industrial robots precisely performing repetitive tasks. The hall is spotlessly clean, with perfect order and harmony. At any moment I can increase production or introduce some extraordinary innovation. I feel like Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański in his 19th-century factory in Łódź. Why did I choose the “Wholesale” model? Because I toured that factory and I liked it.

Unfortunately, pragmatism can be merciless. What the heart tells us is not always the most effective solution. In other words, sometimes, by making a bit more effort, we can achieve twice or even three times the profit. And here lies the problem: human nature—with its baggage of emotions, experiences, and fears—can hinder rational decision-making.

In such moments, mathematics comes to the rescue. It allows us to set emotions aside and look at the problem with a cool, analytical eye, enabling the choice of a strategy that will bring maximum benefits. Thanks to this, instead of relying solely on dreams, one can choose a solution that ensures real efficiency and stability in the longer term.

Mathematics, i.e., DEA-CCR

The DEA-CCR method was developed in 1978 as a tool for assessing the efficiency of decision-making units. In short, it serves to compare objects or organizations that seem incomparable. The main evaluation criterion is efficiency in achieving a defined goal. For example, we can compare four different vehicles: a tractor, a bus, a scooter, and a passenger car. At first glance, these means of transport appear completely incomparable because each serves a different function and has different applications. However, thanks to a mathematical approach, we can assess which of these vehicles is the most optimal under given conditions and for accomplishing specific objectives. Such a comparison takes into account key parameters such as fuel consumption, capacity, speed, and operating cost, which allows us to choose the vehicle best suited to the task.

DEA-CCR consists of calculating the relative efficiency of decision-making units by comparing their inputs and outputs. For each unit, the method forms an efficiency frontier (the “frontier”), i.e., a set of units that make the best use of their resources. Units on this frontier are considered efficient, while those outside it are inefficient. Efficiency is expressed as the ratio of a virtual sum of outputs to a virtual sum of inputs, where the weights are chosen to maximize the result for each unit.

What makes DEA-CCR unique is its ability to account for many different input and output variables without the need to simplify or aggregate them.

In the context of choosing a business strategy, DEA-CCR is particularly useful because it allows evaluating the efficiency of different options in a multidimensional way. For example, in analyzing a bakery’s strategies, the method can include various aspects such as operating costs, labor intensity, receivables turnover, or profitability. Each strategy is evaluated against the others, which helps identify which one uses available resources best to maximize results.

DEA-CCR eliminates subjectivity in the strategy selection process because it automatically determines optimal weights for each unit’s inputs and outputs. Thanks to this, it not only points to the most efficient strategies but also indicates what changes should be introduced in less efficient options to improve their own efficiency.

Choosing a Strategy Using DEA-CCR

For the purposes of this example, I prepared a set of decision variables that may play a key role when choosing a strategy. These factors are presented in the table.

For turnover measured in cycles, a higher number of cycles per month (or year) is preferable. This means the company converts receivables into cash more quickly, which translates into better financial liquidity and more efficient working-capital management. Accordingly, in the table “receivables turnover (cycles)” remains in a form where higher values are better. The “level of calm” is an indicator that describes the degree of harmony and stability in the company’s functioning. It is the inverse of the level of stress, where higher values mean less operational tension and greater ease in managing business processes. The level of calm can be understood as a measure of operational comfort that enables the company to function more smoothly without excessive disruption.

Here is the task implemented in Python.

STEP 1: Define inputs and outputs.

• Inputs: operational factors that require resources (labor intensity, number of office employees, costs).

• Outputs: business effects, including both positive (profitability, stability) and negative (stress).

STEP 2: Prepare the data. Negative outputs (e.g., stress) are transformed into negative values so that they are included in the analysis as “undesirable.”

STEP 3: Implement the DEA-CCR model. The dea_efficiency function calculates efficiency for each strategy by comparing ratios of inputs and outputs.

Parameters

| Parameter | Supermarkets | Own stores | External stores | Wholesale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs | ||||

| Labor intensity | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Number of office employees | 10.0 | 20.0 | 15.0 | 2.0 |

| Fuel costs (PLN) | 15,000 | 12,000 | 10,000 | 5,000 |

| Total costs (PLN) | 500,000 | 700,000 | 450,000 | 300,000 |

| Outputs | ||||

| Sales profitability (ROS) | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| Level of calm | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Level of stability | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Receivables turnover (cycles) | 5.0 | 10.0 | 8.0 | 12.0 |

STEP 4: Compute efficiency. We call the function and calculate the efficiency of each strategy.

Result

Summary

Based on the DEA-CCR analysis results for the bakery strategies, the following conclusions can be drawn for the owner of a plant producing pastries and bread.

1. “Supermarkets” strategy

• Efficiency: high (e.g., 0.79 compared to other strategies).

Conclusions:

• This strategy is stable despite the low margin. Cooperation with supermarkets ensures regular orders but requires large investments in a vehicle fleet and the hiring of drivers and technical service.

• The stress associated with this strategy is high, which may affect company management in the long run.

• It is worth considering as a primary option if the priority is stability with limited possibilities for sales planning.

2. “Own stores” strategy

• Efficiency: average (e.g., 0.71).

Conclusions:

• The strategy provides higher profits (higher sales profitability) but is more complicated to manage.

• It requires high operating costs such as renting premises, maintaining a vehicle fleet, and store staffing.

• The instability of store leases and labor intensity can be challenging; therefore, this strategy should be chosen by an owner experienced in managing retail networks.

3. “External stores” strategy

• Efficiency: relatively low (e.g., 0.56).

Conclusions:

• Although this strategy is more profitable than cooperation with supermarkets, its efficiency is limited by the need to maintain a vehicle fleet.

• This model does not require hiring store staff, which reduces managerial burdens.

• It may be a good solution if the bakery has limited human resources, but in the longer term it may be less competitive.

4. “Wholesale” strategy

• Efficiency: lowest (e.g., 0.18).

Conclusions:

• This strategy requires the fewest resources (employees, fuel, and planning), but its efficiency is low due to limited margins and smaller revenues.

• It is an option for an owner who wants to simplify operations and reduce operating costs but must accept lower profits.

• It can be useful as a complement to more complex strategies or in crisis situations when the company wants to minimize risk and costs.

The owner should choose the strategy that best fits their resources (financial and staffing) and long-term business goals.

This is, of course, only an example of applying the algorithm, and the data were selected at random, based on the author’s limited experience. This analysis should not constitute the basis for making actual business decisions. Nevertheless, the algorithm can easily be adapted by substituting real data on variables and decision factors that matter when choosing a strategy.

The strategy model was written in a universal way, so one only needs to enter their own data. It is worth remembering that business decisions should never be made under the influence of emotions.

The analysis showed that my vision of being a great industrial producer, controlling every aspect of operations, turned out to be the least efficient. Had I chosen this strategy under the assumptions formulated in the task, I would have incurred high opportunity costs. In the longer term, this could lead to a loss of the company’s financial liquidity, threatening its stability and future.

This example is a reminder of how important it is to make decisions based on reliable data analysis, not merely on subjective beliefs or visions.

Wojciech Moszczyński

Wojciech Moszczyński—graduate of the Department of Econometrics and Statistics at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń; specialist in econometrics, finance, data science, and management accounting. He specializes in optimizing production and logistics processes. He conducts research in the development and application of artificial intelligence. For years, he has been engaged in popularizing machine learning and data science in business environments.